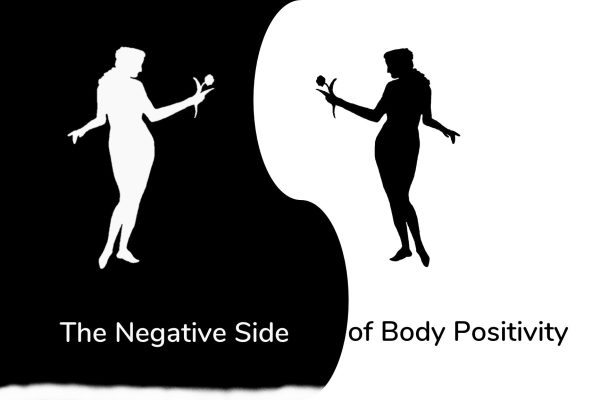

The Negative Side of Body Positivity

23 January 2020 | Theme: Body | 6-Minute Read | Listen

When I first heard of the body positivity movement, I thought, “It’s about time.” It seems like such a simple idea: all bodies are different, so all bodies should be accepted and even celebrated as they are.

“Body Positivity.” It sounds—you know—positive.

So what can possibly be the down side to becoming more positive about our bodies?

I’m all for allowing all people to feel good about the bodies they are in. But when it comes to feeling good about our bodies, we’re up against a lot: the “beauty ideal” is a societal construct that is anything but constructive—it shames and demoralizes any woman who can’t live up to it. Women are expected to be young, smooth, high cheek-boned, light skin-toned, slim-waisted, full-busted, and small-footed. (I’m aware that there’s a whole other set of expectations surrounding men’s bodies, but I live in a female body, so I can only speak to the pressures I feel.)

Our society spends over $18 billion per year advertising cosmetics alone—ads aimed at making us feel dissatisfied with our blemishes, age spots, lip color, scent, or eye shape. The weight loss industry spends over half a billion dollars just on television ads, with billions more in print and internet ads, all aimed at making us uncomfortable in the skin we’re in. The goal, of course, is to motivate us to buy products claiming to “fix” these “problems” so that we will continue to feed these industries that are already worth nearly $200 billion.

So a body positivity movement that pushes back against all that seems like a great idea. Except that, as a “movement,” it’s bound to get political. And it has. But to understand all that, we need to look at where “body positivity” comes from.

We can look back to the Victorian Dress Reform movement of the 1850s to 1890s as a possible beginning. According to Lux Alptraum, activists fought the restrictive and even damaging dress standards of their day, arguing that “women shouldn’t be forced to mutilate their bodies with overly-restrictive corsets or bury their legs under mountains of petticoats.” In the 1960s, “the focus began to shift from fashion to fat shaming,” and the movement became about Health at Every Size. As hashtags and social media campaigns became popular, the “movement” shifted to become more inclusive, “expanding our ideas of beauty to include people of all gender identities, races, sizes, ages, and abilities.” Some women use the term “body positivity” to mean accepting their flaws or being happy with their bodies. That’s where it gets political.

Some argue that thin women can’t be “body positive.” They reason that “body positivity” is, at its roots, “fat acceptance,” so thin people aren’t allowed. How’s that for a double standard? Some even carry it to a potentially dangerous extreme: you aren’t being positive about your body if you are intentionally trying to lose weight—even if you are trying to improve your health! Even more hypocritical: some plus-sized models have to wear body padding because they aren’t “large enough.” How, I ask, is that any different from a thin model wearing a corset to appear thinner?

Believe me, I get it. Size discrimination is seen in employment, health care, and education, and body size is treated as a moral issue. Food is categorized as “good” or “bad,” and larger bodies are “stereotyped as lazy, unmotivated and sloppy” (Brown). So it is important to let women who have spent their lifetimes being labeled as “overweight” or “obese” know that they are worthy of feeling good about their bodies. Shifting the paradigm to Health At Any Size makes sense. The most important things, after all, are health, vitality, and energy.

But those who stir up controversy about who’s “in” and who’s “out” of the body positivity sphere are completely focused on appearance. Isn’t that what the movement was pushing against to begin with?

And what about health, vitality, and energy? Some extremists insist that weight doesn’t matter at all—that it has nothing to do with health. That simply isn’t true. Diabetes, hypertension, and infertility are all affected by body mass, and it’s irresponsible to pretend otherwise.

As “body positivity” gets co-opted by brands and influencers, many former adherents are stepping away from the movement. In some cases, that’s because the movement has become too narrow—often focusing only on one aspect of body positivity but still promoting a limited view of beauty. What happens if you are large AND have imperfect skin AND have a disability? Or you are aging? Or are a woman of color? Or have cellulite? Or what if you have a body that others see as the stereotypical standard of beauty? Are you excluded from being positive about your body?

Finally, the worst part of body positivity as a movement is that it heaps more guilt and shame on women. As Heather Widdows points out, “Feeling ashamed of our bodies really is being ashamed of our selves. If we are feeling shame, telling us we shouldn’t feel like we do can make it worse. It can make us more guilty.” Thus, the unintended consequence of a movement that was started to make women feel good about themselves is that it can backfire and leave them feeling even worse about themselves.

I have decided that it’s up to me to decide what I mean by Body Positivity. I don’t have to follow a movement to feel good about the body I’m in, to love it and treat it well. I agree with Amber Petty, who said, “True body positivity means you can do whatever you want with your body as long as you do it with love. Some people do need to lose weight for their health, and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that. Others want to lose weight to look different—and that’s their right. If you aren’t obsessed with losing weight, then I don’t think it’s a problem.” I would add that remaining exactly as they are is also their right.

If we love our bodies, we nurture them. We take them to the doctor for regular check-ups. We move them. We fuel them with mostly nutritious foods. We treat them once in a while to an indulgence. We make them strong. We marvel at all they do for us. We don’t criticize their every flaw or attack them for what they are not. As Gwenda Sharp said, we celebrate them.

Until next time,

Resources:

Alptraum, Lux. “A Short History of ‘Body Positivity’.” Fusion, 6 November 2017. https://fusion.tv/story/582813/a-short-history-of-body-positivity/

Brown, Gretchen. “Why the Body Positivty Movement is Turning Some People Off.” Rewire, 17 January 2019. https://www.rewire.org/living/body-positivity-movement-turning-people/

Petty, Amber. “Is the Body-Positivity Movement Going Too Far?” Greatist, 25 January 2018. https://greatist.com/live/body-positivity-movement-too-far#1

Sharp, Gwenda. “A Conversatioon with… Gwenda Sharp.” DoYouMind.life Podcast, 4 January 2020. https://do-you-mind-podcast.blubrry.net/2020/01/04/a-conversation-with-gwenda-sharp/

Widdows, Heather, Ph.D. “What’s Wrong With Body Positivity?” Psychology Today, 2 July 2019. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/perfect-me/201907/what-s-wrong-body-positivity

If you enjoyed this article,

please share on social media!

NEXT ARTICLE

Love Letters to My Body

28 January 2020 | Theme: Body | 6-Minute Read

We live in a culture that is obsessed with bodies—and not in a good way. There are so many mixed messages about our bodies: first, they are miraculous, amazing pieces of art, but we are made to feel disgust for what they produce. Digestion, elimination, and reproduction are normal human . . .