Speaking Up

8 August 2019 | Theme: Voice | 7-Minute Read | Listen

The little girl jumped off her bike, allowing it to fall to the street. She paid no heed to whether her beloved pink bike would be scratched or her handlebar tassels torn; she ignored everything but the fire that burned in her gut as she strode toward the man in the suit. “Stop it!” she yelled at him.

He turned toward her, stunned, the dog’s leash still in his hand even as the dog lay there whimpering. Enraged, she pointed at the poor creature and continued, “You have no right to kick that dog! No matter what he’s done, he doesn’t deserve to be hurt by you!” She was shaking now, frightened by the ferocity of her rage and the authority in her own nine-year-old voice. But she didn’t back down.

The man snapped at her, “It’s my dog. I can do what I want,” and turned to walk away.

She ran to face him again. “No, you can’t. You’re a horrible man to kick an innocent dog, and if I ever see you do it again, I’m calling the SPCA or, or the police, or somebody. You can’t go around treating poor animals like that!” Not knowing what else to say, she picked up her bicycle, jumped on it, and pedaled away. She wanted to be far, far from this man before her tears began to flow.

That little girl was me.

I had been taught to be a polite girl and to respect adults. I used all the well-mannered words, and I stayed quiet when adults were talking. But that day, when I saw a neighbor mistreating his dog, I was compelled to speak up, and I was as shocked as he was to hear my own voice telling him off.

Fast forward three decades. I pulled up to a gas pump and began to fuel my car. As the gasoline filled the tank, I waved and made silly faces at my twins, who laughed and waved back from their car seats. A red pickup truck pulled up on the other side of the pump, and a man in a ball cap jumped out and, leaving his engine running, began to fuel up his truck.

“Excuse me,” I began, “but you forgot to turn your engine off.”

“What?” he asked, incredulous.

This time I said more forcefully, “Please turn off your engine.”

He scoffed, “I always leave it on.”

That raised my mama-bear hackles! Pointing my finger at him, I yelled, “Not when Your truck is attached the same tank as My car and My Babies are strapped inside. Now TURN IT OFF!” He was so taken aback, he complied. I finished fueling and got back into my car before I began shaking uncontrollably.

I dislike confrontations, and I have remained silent many times rather than creating a stir. That’s what “good girls” do, right? But I found the gumption to speak up, and speak forcefully, when I was speaking on behalf of an animal or small children—those without voices. So why is it so hard to speak up for myself?

Apparently, I’m in good company. According to the Harvard Business Review, when encountering ethically questionable behavior, exclusivity, or offensive speech, most people do not speak up, and then they justify their inaction. It’s even harder to voice when we are personally offended because we perceive speaking out as a threat to social status, certainty, autonomy, relationship, or fairness.

Self-doubt creeps in. “Am I the only one who feels uncomfortable at that joke? Should I say something? What will they think?” When I’m in that situation, by the time I make up my mind to say something, the moment has passed, and it would be awkward to bring it back up.

But what if I said it anyway? It could look something like, “I need to circle back to something that was said a few minutes ago, because I’ve been sitting here feeling uneasy and I need to clear it up before we move on. It may not have been intended as offensive, but I was bothered by…” The chances of my being completely shut down are pretty slim, and the chances of others appreciating my willingness to address the discomfort are great.

Besides, according to an article in Aleteia, my fear of how others may perceive me is largely in my imagination. Whether or not others agree, they will likely admire my boldness. And I won’t be lying awake at night wondering why I gave my tacit agreement to something I found offensive.

I heard on a podcast somewhere (I wish I could cite it, but it was a while ago) that the first eight seconds are the worst of it. If you can just walk through the first eight seconds of confrontation, the discomfort is usually relieved. Either people agree or disagree, but the most vulnerable time is in those first eight seconds. Even though it is difficult to do, speaking up is absolutely crucial.

To give another example, this one made up (but all too common): you’re walking down the street and some guys make a rude comment about your appearance—loud enough that you know that they intended for you to hear it. It feels icky. In that moment, you have to decide what to do. If you keep walking and pretend you didn’t hear it, you still feel icky about it weeks, even months later. But if you turn around and say something, it feels icky for about eight seconds, and then you move on. The point isn’t to change them—good luck with that anyway—the point is that speaking up changes you. You’ve stood up for your own boundaries. Way to go!

The Harvard Business Review gave three suggestions to follow when you feel the need to speak up.

First, it said, recognize that it is a difficult thing. People who expect a task to be challenging are more likely to follow through with it than those who expect it to be easy. But keeping in mind that the first eight seconds are the most difficult, you’ll know that you can get through it.

Second, you can reduce the social threat of speaking up by telling the other how you experienced the comment, whether that was the intention or not. So that could be, “You may not have meant it this way, but your comment sounded racist to me.” Or you could approach it by drawing on the relationship: “Our friendship matters to me, so I need to talk with you about a comment you made.”

Finally, making a plan ahead of time can ease the awkwardness of speaking in the moment. You can think through how you might address a recurring situation at work, for example, or a relative who always brings up politics at the holiday table. I’m not talking about getting in the perfect zinger—as good as that feels in the moment, it usually leads to regret. I’m talking about giving honest feedback and setting a clear boundary in a way that allows the relationship to move forward.

Little-girl me and mama-bear me spoke without rehearsal or forethought: the moment presented itself, and I acted from the gut. The crying and shaking afterward? That was left-over adrenaline that had nowhere else to go. But I had to do it because I was speaking for those who couldn’t speak for themselves, and the desire to address cruelty and to protect my children was far greater than any fear I had.

If you, Dear Reader, have times when you wish you could speak up—and most of us do—try talking about it with a trusted friend. Rehearse all the ways you could handle it, including remaining silent. Practice the zingers and one-liners, just to get them out of your system, but then try finding a way that feels right to you. When the time comes, speak from your center, from your core values, knowing that speaking up feels vulnerable, but that you can get through it.

Until next time,

Resources:

Rennier, Fr. Michael. “Why You Should Speak Up—Even When It’s Difficult.” Aleteia 2 Sep. 2018. Web. 7 Aug. 2019.

Smith, Khalil et al. “How to Speak Up When It Matters.” Harvard Business Review 4 March 2019. Web. 7 Aug. 2019.

If you enjoyed this article,

please share on social media!

NEXT ARTICLE

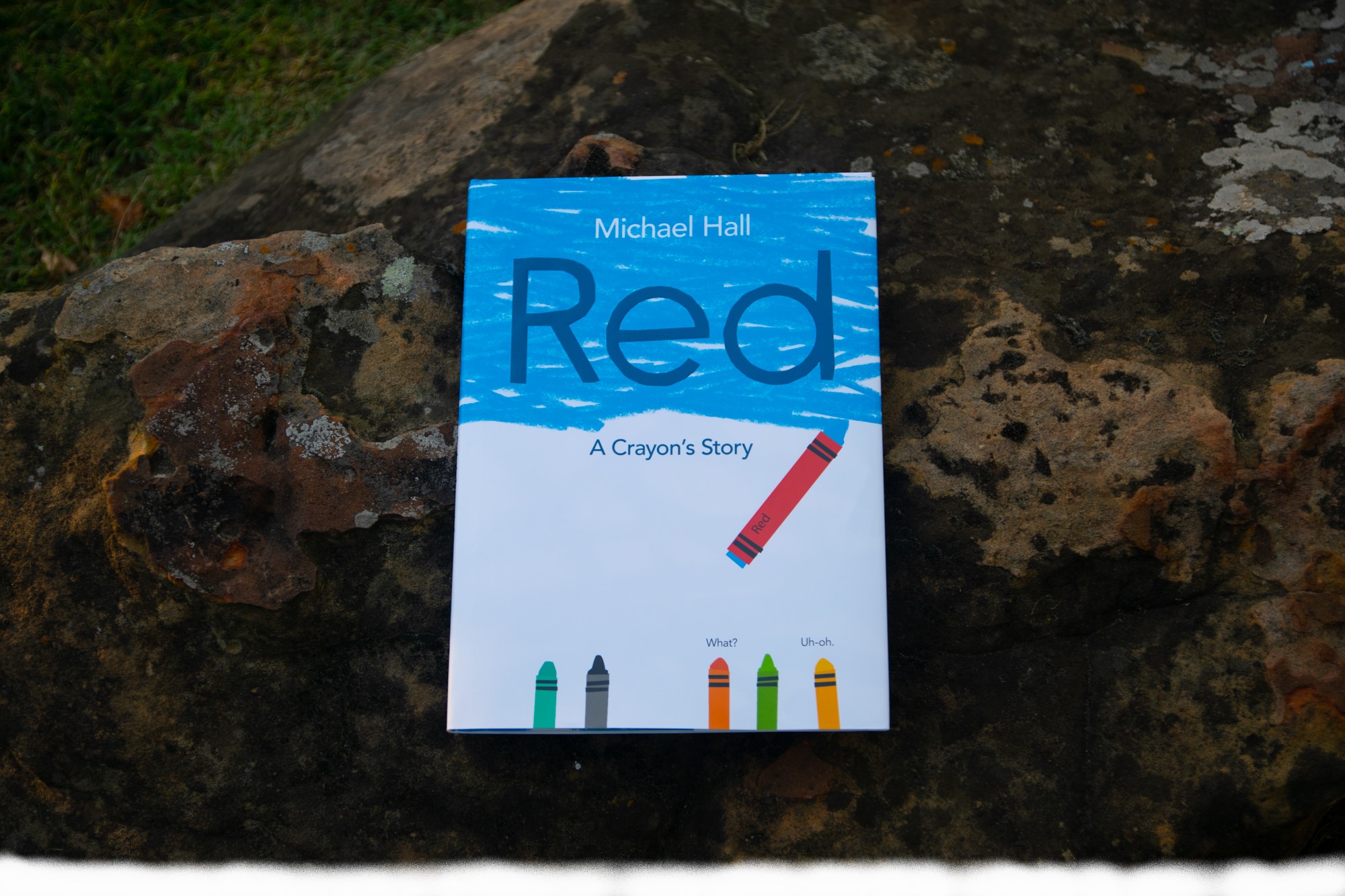

Book Review: Red: A Crayon’s Story by Michael Hall

12 August 2019 | Theme: Voice | 4-Minute Read

Red just can’t seem to get it right. He tries as hard as all the other crayons, but every time he attempts to draw a strawberry, firetruck, or ant, it comes out all wrong. Everyone is concerned and offers help. His grandparents think he . . .