Body of Evidence

7 January 2020 | Theme: Body | 13-Minute Read | Listen

I have a body. Yep. And you have a body. That’s undeniable fact. Having a human body is a prerequisite for having this human experience. So why is it that most of us have so much baggage about our bodies—how they look, work, feel, and even smell?

I could go off on another diatribe about the millions of dollars spent every year on advertising to create dissatisfaction with our bodies so that we’ll shell out billions of dollars on weight loss, skin and hair products, cosmetics, etc. I could speak again to the #metoo experiences that many girls and women experience that cause us to become distanced from our bodies. But I did that back in October with my articles “Enoughness” and “Shame Body,” so today, I’m talking about the stories I believed that shaped my own body image.

Before I continue, I want to assure you that the stories I offer are no longer raw, but have healed or are being healed; I believe that sharing such stories is the path to wholeness for all. It is my sincere hope that my opening up and telling of my experiences will embolden other women to sit with their own stories, to feel them, and to heal them.

This is my story of my relationship with my body.

A few weeks ago, my brother said to me, “Sis, I’ve been thinking about something. When we were growing up, I think we all told you how smart you were, so you grew up knowing that you’re smart. And your creativity and talent were praised, so you grew up knowing that you are creative and talented. But I don’t think you grew up believing that you’re beautiful, and I want to tell you that you are. You’re beautiful.”

My immediate tears testified to the truth in his words. My core belief throughout my lifetime has been that my body is Not Enough, and although I’ve been actively working over the last few years to shed all my body image baggage, I still carry some along. It’s a work in progress. So what’s inside those bags? When did it begin?

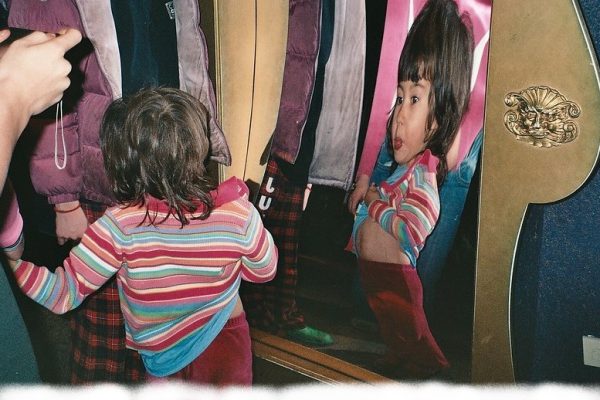

In “Shame Body,” I revealed one of my earliest memories—of being told by the “big boys” up the street to take off my clothes. (You can read the specifics of that incident under “Enoughness” on DoYouMind.life.) The feelings I recall were of fear and shame, even though I was too little to understand why I felt ashamed. But an early imprint was made: bodies bring shame and pain.

A few years later, I sat on the stage at my kindergarten as we rehearsed the Thanksgiving play. (It wasn’t PC at all by today’s understanding, but it was the 70’s.) I was proud of the Native American-style smock my mother had made for me, and as I played with the fringe along its hem, I must have thought I looked cute in it. I was seated next to a girl I’ll call “Kim.” Kim was “that girl”—you now, the one everyone knew would grow up to be a cheerleader, queen of the class, and Miss Popularity.

As my section of the class sat awaiting our turn to perform, Kim looked at me thoughtfully and said, “You know, Stacey, you’re lucky. I’m pretty now, so I’ll be ugly when I grow up. But you’re ugly now, so you’ll be pretty when you grow up.”

I have no idea why she said it. What makes a child say such a thing? Maybe she had read The Ugly Duckling and was trying to make sense of the story. And to be fair, when we were about to graduate from high school, though we had never become friends, she and I were talking, and I asked her if she remembered what she had said to me in kindergarten—I had certainly never forgotten. She had no memory of it, and she was shocked that she had ever said such a thing. She apologized profusely, and I forgave her. But that didn’t change what had happened. It didn’t change the story I had formed in my own mind.

Sitting on that stage, I was stunned. I thought, “You mean I’ve been walking around ugly my whole 6-year-old life, and nobody has told me?” I believed her, of course, because this is what we do: we ignore everyone else who has ever said something positive and we focus on the one person who says something negative. Around Kim’s cruel, thoughtless words, I formed the story that I wasn’t pretty.

As I entered puberty—earlier than most of the other girls—I began to get curvier. I hated my curves. I didn’t want breasts yet; nobody else had breasts. In fifth grade, I’d had a growth spurt so that I was the second tallest girl on the basketball team. But by sixth grade, the other girls had caught up in height, and I noticed in tryouts that running up the hardwood was more painful because my breasts bounced. I didn’t even make the team that year. New addition to my story: I’m not athletic.

I recall shopping for fabric with my mom when I was in junior high school. My mother was a wonderful seamstress; she could sew beautiful clothes. At the fabric store, I admired some suedecloth for the millionth time. It was gorgeous—so soft, and such a rich, deep texture, and the color was a beautiful buff that I just knew would look stunning if made into a dress or skirt. I wanted that fabric! But it was expensive, and not very practical for everyday wear.

I’m sure my mother wanted to get me that fabric. She also wanted the best for me; she must have been concerned about the rapid changes in my body. In a misguided attempt to encourage me, she said, “I’ll get you that fabric and make you a dress as a reward when you lose ten pounds.” This new information reconfirmed the earlier story, and added yet another layer: I’m too fat to deserve pretty new clothes.

I hated going shopping for clothes because standing in the dressing room was humiliating. Any time clothes were too tight here or there, it wasn’t because the clothes were wrong—it was because my body was wrong. It was pointed out that I was having to move more and more to the right of the clothing racks, to the larger sizes. I began to want clothes that would hide me, camouflage my too-muchness. I wanted to be noticed, but only for the things I felt confident about: intelligence and creativity. I didn’t want to wear homemade blouses with slacks. Please, oh, please, just let me wear jeans and t-shirts like the others! And a pair of Nike sneakers. If I can dress like everyone else, I’ll blend in, and maybe nobody will notice that I’m getting so heavy.

When I was in ninth grade, I was nominated to be in the homecoming court, along with four other girls who were all “that girl.” I knew that I was NOT “that girl,” so I wanted to decline the nomination. I was convinced that the boys on the football team who had nominated me were making a joke of me. It was going to be like “Carrie,” except that I didn’t have any special powers to unleash if they started to jeer at me. I was so inside my own story that I couldn’t accept that they had nominated me because they liked me.

By the time I finished high school, I had found a great way to handle all that body image baggage: I separated my “self” from my body. My mind and “I” were over here, and that “body” thing was over there. If I could objectify my body, then maybe it wouldn’t be so painful when I heard all those messages designed to make me even more dissatisfied with the way I looked. Mind and I would carry along just fine, thank you very much, and that body thing would just have to tag along while Mind and I ignored it.

My body insecurities stayed with me into adulthood, informing my dating life, my marriage, and my motherhood.

I now think that a major reason that I had difficulty getting pregnant was this dissociation with my body. I wanted children so much, but my body—the body I had ignored, blamed, and despised for all these years—didn’t want to allow me to bear them. Maybe it wanted me to reconcile with it before I expected it to bear the gift of offspring. I was at odds with it even as I put it through the rigors of fertility treatments.

Then, there was a period of blissful truce: I was pregnant, and I loved being pregnant. I loved the feeling of life growing within me. I loved that my body was designed to keep my twin babies safe until they were ready to enter the world.

At 29 weeks, though, my body wasn’t able to keep them safe any longer. I developed preeclampsia, and my babies had to be taken by emergency C-section. Again, Body had failed: couldn’t get pregnant, couldn’t stay pregnant, and now, because of my body’s Not-Enoughness, my two tiny preemies were struggling for life. As I watched them in the NICU, I blamed my body for their struggles. They’re strong and healthy college coeds now, but at the time, there was no way to know that everything was going to turn out well. All I could see was that their tenuous start in life was All. My. Fault.

It has taken me years, but I have been able to unpack a lot of the baggage I have been carrying about my body. As I said before, it’s a process, and it’s ongoing. The first part of my process has been to take out each piece of “evidence” I have held—really see it—and understand how it has contributed to the way I see myself today. In order to see each story, I have to peel back the layers of beliefs that I formed around it. It’s like peeling back an onion layer by layer; each one stings the eyes.

The next step on my journey is to let go of the beliefs that I have held. Sometimes the letting go is easy—as soon as I recognize a false belief, it evaporates in the light of day. Other times, though, the belief is so interwoven within me that letting go requires unraveling many stories. I suppose that’s why there are several false beliefs that I can recognize but I can’t quite let go. I want to, but they are still tangled up within me. The best I can do when some new event tugs on the old belief is to acknowledge it—“Ah, there you are again, Old Belief”—and allow it to tag along. At least by accepting that it’s there, I’m not wrapping the new event up in the old paradigm.

Finally, I create a new set of beliefs. I look for ways to celebrate my body, to embrace it and thank it for all it does for me. This is the one body I get to have for this lifetime, so I want to care for it, nurture it, love it—as it is Right Now. It doesn’t have to lose ten pounds to be deserving of new clothes. I can hike, ride a bike, dance, and love my body today. I can enjoy eating healthful—and sometimes not-so-healthful—foods and savor the pleasure that this body brings.

Through this journey toward greater self love, I haven’t been alone. I’ve been fortunate to have amazing support at every step along my way. My “tribe” encourage me and fortify me. They nudge me when I need reminding, and they reframe for me when I need to shift an old belief. I am forever grateful to each of them.

While my story is my own unique set of circumstances, the story itself is fairly universal. We all have our insecurities. I am sure that all those girls who were “that girl” had their own struggles. In fact, while I was chatting off-air with my next podcast guest, Tamara Greenberg, I shared with her some of the content that I would be including in this article. She asked me, “So what did believing that you weren’t beautiful allow you to do that you couldn’t have done if you had believed otherwise? Where was the gift in that?” As I thought about it, I realized that without the pressure of appearance, I got to excel academically. While those other girls were stuck in the cage that others expected them to fit into, I had the freedom not to have to “dumb myself down” to fit into the stereotype of “pretty girl.”

So what is your story of your relationship with your body? What were the early experiences that informed your beliefs? Could sharing your story help you to heal old wounds? Could it help others? I believe what Brené Brown says about shame: it can only survive in darkness and secrecy. Sharing our stories shines a light on them, and they no longer dictate from behind the curtain. Ultimately, your story doesn’t separate you, though Shame wants you to think it does. Shame convinces you that you’re alone so that it can survive. But know this: your story CONNECTS you to other women.

I invite you, gently, kindly, and with tremendous compassion, to sit with your story, and when you’re ready, to share it with others.

Until next time,

If you enjoyed this article,

please share on social media!

NEXT ARTICLE

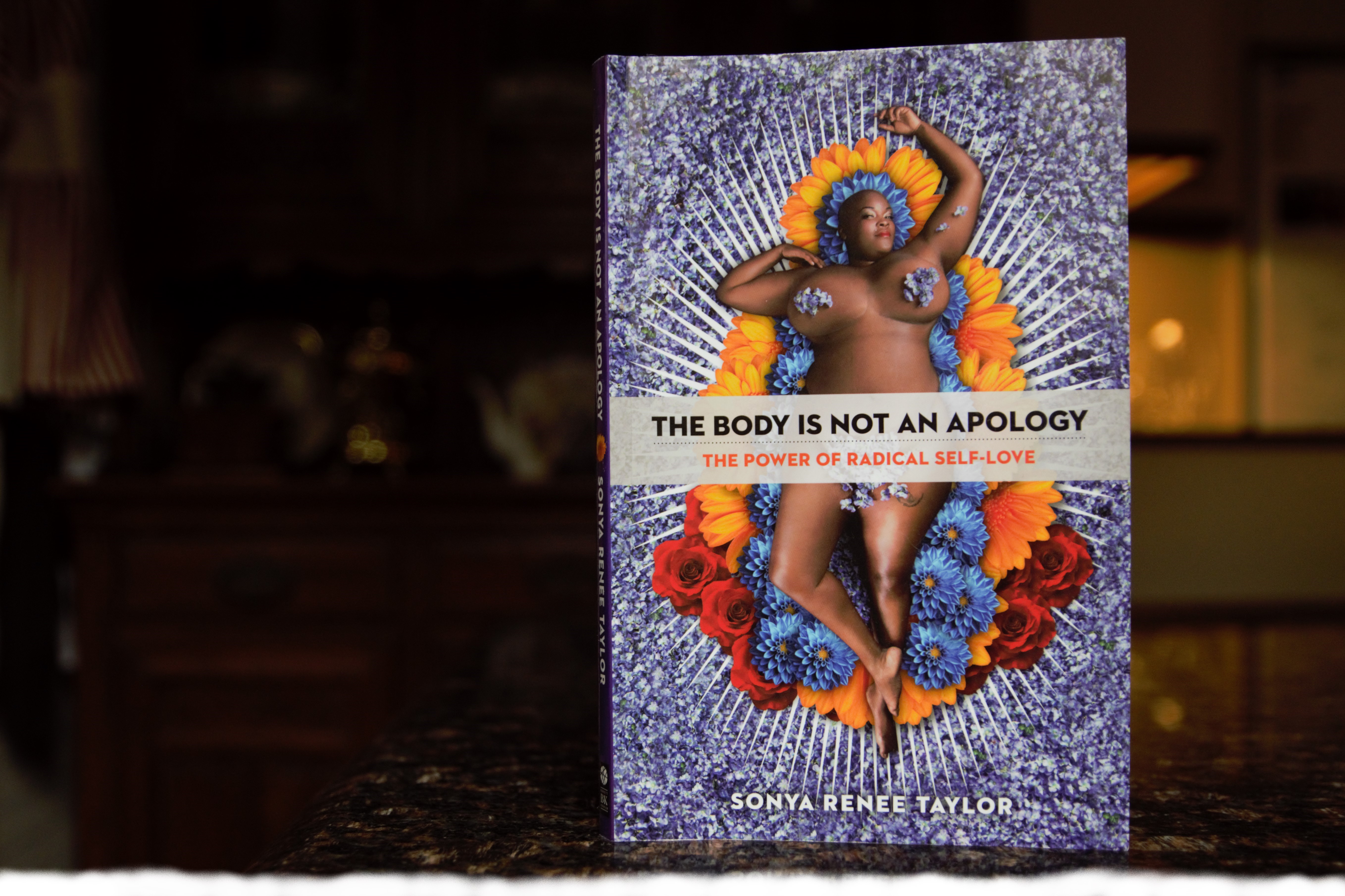

Book Review: The Body is Not an Apology

by Sonya Renee Taylor

9 January 2020 | Theme: Body | 5-Minute Read